Here’s my analysis of LinkedIn’s onboarding process.

Persona: A new professional seeking to join well known professional networking platform called LinkedIn. She works at a company and heard about LinkedIn from co-workers. She knows that she can add her co-workers, find jobs, and post status updates on LinkedIn. Hence, over the weekend, she opens up the internet browser, enters www.linkedin.com, and lands on the website.

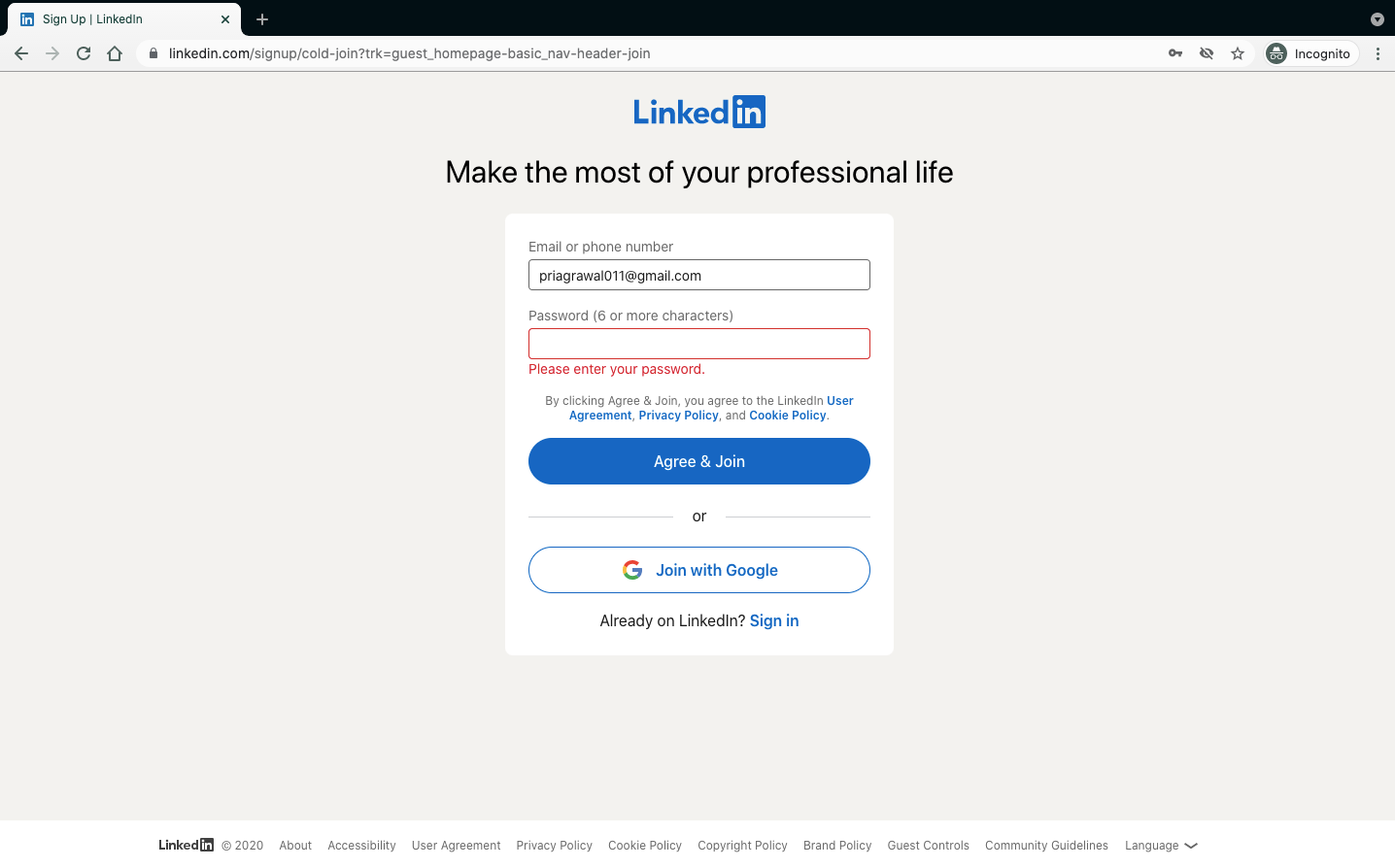

Once I click on ‘Join Now’ on www.linkedin.com, the website takes me to a webpage to enter the email address or phone number and set a password. When I set a password with no large CAP or special character, it was slightly concerning to me that it is possible that my account can be hacked easily. On the flip side, setting an easy password reduces the cognitive effort, thereby reducing friction in the process. I click on agree & join, without looking at terms & conditions, and proceed further. View: I would agree that setting a password is easy, and a new joiner will not be heavily concerned about account hacking because she has not yet entered any sensitive information on the website. However, once user engagement is significant, I would recommend to the user to set up a stronger password to protect the account.

Once I agree and join, the website asks me for my first name and my last name. I have the liberty to add just my initials. The website does not give me any guidelines on best practices such as ‘It is recommended to add the complete full name and the complete last name’ as it helps in building a ‘trustworthy online profile’. Regardless, I enter the data, which takes me to a page meant to avert non-human sign-ups. The only change I’d bring to this step is nudging users to enter high-quality data (full name and last name). Engineering effort is low - as it is only a ticker type of one-liner that shows up during data entry. The expected outcome is that users provide higher quality data that would help in building a trustworthy profile which in turn improves user engagement, simply because nobody likes to connect with a shady-looking, possibly fake profile. This nudge also trains the user in online personal branding using a small step. Let’s move to the next step.

The website asks me for my location using two data points - Country/Region, and City/District. I would reduce this to just City/District with a fair assumption that LinkedIn, by now, would have a very large database of locations to cater to global users. Country/Region can easily be implied from City/District when the search results of City/District show options that already contain Country/Region. This would reduce friction in the onboarding process; the engineering effort required to disable a field on a screen is low. Let’s jump to the next step.

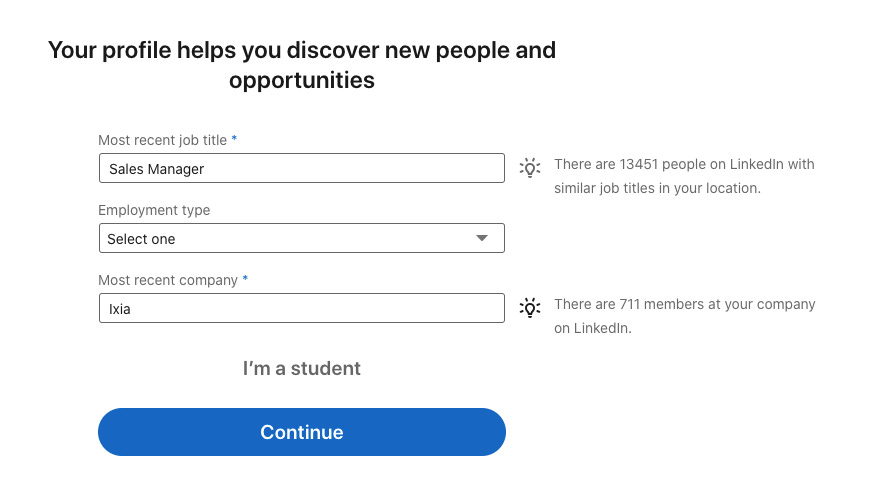

LinkedIn asks me to enter three professional details, namely the most recent job title, employment type, and most recent company. I would remove ‘Employment Type’ from the page. If a field is optional, it is not important. The other two fields make sense, with a small change to the analytics that shows up. When I see that there are 13451 people on LinkedIn just like me, it makes me feel slightly relieved that I will fit well in the network, but it also makes me feel concerned that there is significant competition in the job market. Instead, saying that ‘There are 10,000+ people on LinkedIn with similar job titles in your location is a larger range of the competition. Alternately, one could show a metric on the number of job applications that similar profiles have made on the website, or the number of jobs available for similar titles - which are more attractive as a user.

When I click on the ‘Continue’ button, the website asks me for the location and the job title for which I would like to see open job positions. Once I enter the information, the job results show up on the job search page. This flow assumes that the first thing I want to do on the website is applying to job openings. The positive point of this step is that time to value is quick - even when I do not want to apply to jobs immediately. I can browse through the search results, and see their quality and relevance to my career. If one had to ‘add friends’ to connect with, time to value is pushed further because the returns from a useful network take time and situation.

This last step of the onboarding process to show quick time to value is critical. Following are a few ideas to experiment with:

Show courses to enroll in, in addition to, job openings - Relevant, affordable, or free courses can be highly engaging and show quick time to value.

Show option to follow senior leaders of the user’s company, and show their posts. This is likely to get users to engage in ‘Liking’ posts which is a reward in itself.

Since the user is in sales, recommend purchasing a sales navigator license upfront. It will be a great product introduction to a relevant buyer persona, also showing quick time-to-value.

Ask for the current salary upfront. This can be helpful information to LinkedIn in the larger business context (such as the ability to pay for a premium account, industry knowledge as such, information worth sharing with recruiters, etc). While asking for this information could possibly see a drop in competition % of onboarding, it is worth experimenting because people tend to divulge more information when they have less idea about how the data could be used. This sounds sneaky, but in return, if you give back salary information (industry standards, function-wise, etc), it is a win-win situation for everyone.

Thoughts?

(I suppose this warrants another post evaluating the four options and prioritization, for specific metrics such as completion % of onboarding, or LTV).